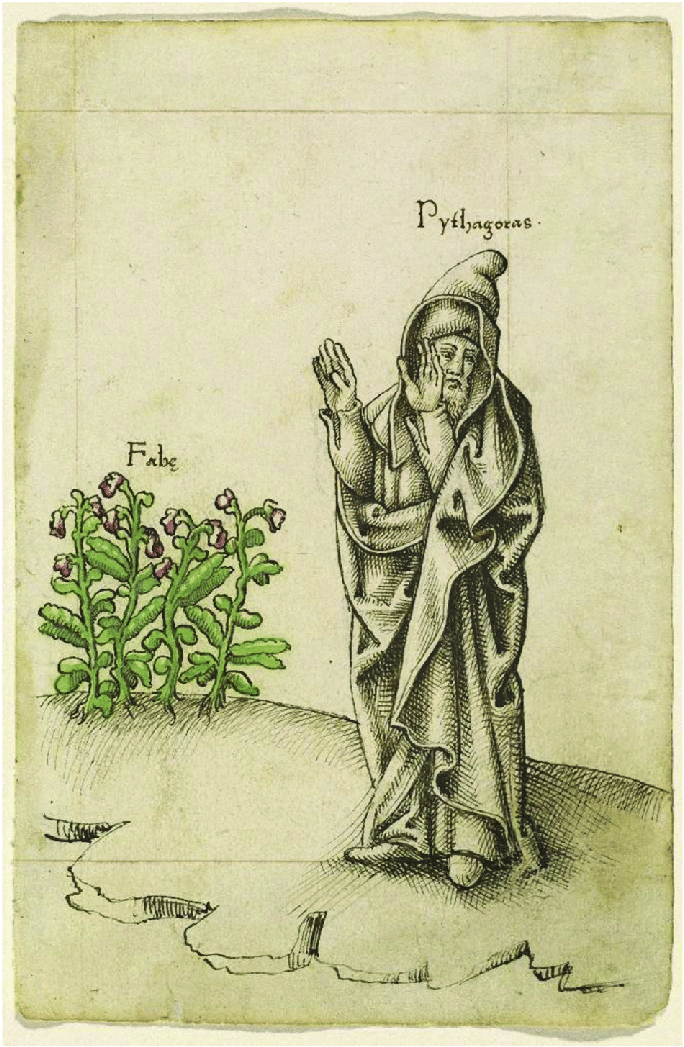

How do you feel about Pythagoras’s theorem? I always insist that it is annoying knowledge which is taking up a slot I could use for something else so I was pleased to find out that the originator of this theorem wasn’t just stuck in a room creating irritating maths equations but actually had a whole other side to him. Pythagoras, who hailed from the Greek island of Samos, was born about 570 BCE, and dissatisfied with the tyrannical rule of Polycrates he left on his travels through the ancient world, eventually settling to found a kind of counter-culture commune in Croton, part of Magna Graeca, in modern southern Italy. Reputedly about 300 men flocked to his side. There they practiced their mysteries, speculated on the universal truth of numbers (hence the connection to geometry), played music and ate vegetables, honey, bread and, if Porphyry is to be believed, occasionally fish. This vegetarianism stemmed not so much from concern for animal welfare, but from the rejection of violence in general, especially of the sort officially sanctioned by the Greek state – public animal sacrifices and warfare. The comparison to twentieth-century hippie communes is not too far-fetched.

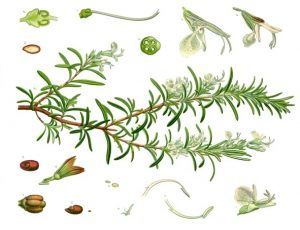

You might notice that there was no mention of beans and pulses, those favourite staples of a vegetarian diet. That was because beans were banned by Pythagoras in fact among the followers of Pythagoras the ban was so strict that even crossing through a bean field in flower was forbidden, and in one account this is how Pythagoras met his death when pursued by enemies – he refused to escape through a bean field and was captured. There are several suggestions for the reason for this ban but the most plausible explanation seems to be around Pythagoras’ belief in metempsychosis, the supposed transmigration at death of the soul of a human being or animal into a new body of the same or a different species.

He believed that beans were part of the whole cycle of reincarnation and that they housed human souls. To eat a bean was thus a form of murder. An Orphic fragment summarises the belief thus: “eating beans and gnawing on the heads of one’s parents are one and the same.” There are even references to a magical trick performed by Pythagoras, as told by Porphyry, that he planted some beans in a pot and after ninety days they looked like a human head – presumably a soul caught in transit and only partially reincarnated.

Due to their black-spotted flowers and hollow stems, some believers (possibly including Aristotle) thought the plants connected earth and Hades, providing ladders for human souls, if you have ever seen broad bean pods protruding horizontally from the plant; they do resemble a ladder. Diogenes Laertius, the Roman biographer of the Greek philosophers went even further and wrote that beans were made of soul-stuff, the same thing that animated human life.

It wasn’t just the Ancient Greeks, although even there Pythagorean beliefs were in the minority. The ancient Romans believed that the plant of broad bean was directly linked with the underworld due to its long roots and stem with little branches, so was considered able to bring the dead back to the world of the living as they could use the ladder to escape the underworld.. The black spots on the flowers were also associated with mourning for the Romans. At Roman funerals, broad beans were spread over the tombs to give peace to the deceased, whereas toasted broad beans were distributed, together with bread, during the dies parentales (“days for celebrating the memory of the family’s dead”). Roman priests for Jupiter weren’t even allowed to handle beans, so strong was their association with death and decay. They were as taboo to the priesthood as the eating of dead flesh.

The connection of beans to death in Italy continues in more recent times through the celebration of All Souls Day. Children in many regions of of Italy are still given fave dei morti, “broad beans from the dead” which are actually biscuits made of ground almonds and sugar, sometimes delicately coloured pink, yellow and brown. Up to the nineteenth century, stewed beans were also still distributed to the disadvantaged on this day particularly in the southern regions.. Dishes like this were known as cibo dei morti (food of the dead) and they also formed part of slightly richer feasts eaten by better off families.

During these celebrations food was given to the destitute because it was believed that they were very similar to the dead as they shared some important characteristics, being deprived of wealth and belongings and in need of assistance. Furthermore, the poor person in need of charity from the public was often without living family, a state recalling the fate of the soul of the departed now separated from living family and friends. In the case of the itinerant beggar, the similarity with the dead is further stressed by the absence of a home: the beggar wanders on earth homeless while the soul of the dead has commenced upon a journey towards the realms of the other world. The symbolic association between beggars and the dead has been documented in Europe since antiquity and is one of the reasons for soul cakes and going souling in the UK.

Featured Image :

Public Domain taken from a French manuscript in the early sixteenth century.

Suggested Reading:

From corpse to ancestor. The role of tombside dining in the transformation of the body in ancient Rome. From The materiality of death. Bodies, burials, beliefs – R Gee

Reconstructing funerary rituals: the evidence of ustrina and related archaeological structures. In Burial, society, and context in the Roman World – Michel Polfer

Beans, A History – Ken Albala

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/favism-fava-beans

Food: A Culinary History – Jean-Louis Flandrin, Massimo Montanari,Albert Sonnenfeld

Symbolic meaning and use of broad beans in traditional foods of the Mediterranean Basin and the Middle East. – A Pasqualone, A Abdallah, C Summo

Bodies of Vital Matter Notions of Life Force and Transcendence in Traditional Southern Italy